I found this article written by John Stevens that I thought was particularly good. Recently, his translation of The Art of Peace by Morihei Ueshiba was featured on the TV show the Walking Dead. I thought it might be appropriate to post this so that students can get an idea of who Stevens Sensei is and how his translation influenced almost every Aikido student in the west.

The Practice of the Way

by John Stevens

Every human being is potentially enlightened; each one of us is a miniature shrine of the divine. But in order to manifest the treasures within, we need a suitable path to follow, proper vehicles for training, and good teachers to point us in the right direction.

The kind of path we finally select as our own Way is not important, but whatever we choose, it must be practiced.

“Practice of the Way” in Japanese is known as shugyo, “hard training that fosters enlightenment.” The purpose of shugyo is “to tighten up the slack, toughen the body, and polish the spirit.”

One aspect of shugyo is keiko, an elegant term that signifies “using ancient wisdom to illuminate the present.” Every Way has a pantheon of illustrious predecessors—trailblazers who established their particular path after passing through dangerous, uncharted territory—who have left us an important legacy. It is that legacy which we encounter daily in keiko.

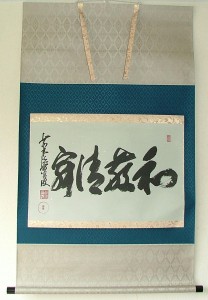

In the practice of calligraphy, for example, a beginning student (after first spending at least three years mastering the basic strokes) is set to work making exact copies of the masterpieces of Chinese and Japanese brushwork. Following ten, or better still, twenty years of reproducing all manner of scripts and styles, the practitioner has absorbed five thousand years of tradition and is now ready to be turned loose to develop a fresh, individual approach.

In keiko, the supreme virtue is patience. Once a young man petitioned a great swordsman to admit him as a disciple. “I’ll act as your live-in servant and train ceaselessly. How long will it take me to learn everything?”

“At least ten years,” the master replied.

“That’s too long,” the young man protested. “Suppose I work twice as hard as everyone else. Then how long will it take?” “Thirty years,” the master shot back. “What do you mean?” the anguished young man exclaimed. “I’ll do anything to master swordsmanship as quickly as possible!”

“In that case,” the master said sharply, “you will need fifty years. A person in such a hurry will be a poor student.” The young man was eventually allowed to serve as an attendant on condition that he neither ask about nor touch a sword. After three years, the master began sneaking up on the young man at all hours of the day and night to whack him with his wooden sword. This continued until the young man began to anticipate the attacks. Only then did formal instruction commence.

A second key element in keiko is kokoro, “heart, mind, spiritual essence.” All technique flows from the practitioner’s kokoro, and no amount of technical skill can compensate for inadequacies caused by an immature, disturbed, or stagnant mind.

Once I complained to a calligraphy teacher that my many obligations prevented me from practicing more. She replied, “Don’t worry. If you are improving your mind, you are improving your calligraphy.” Similarly, practitioners who demand to be taught an art’s secret techniques are told, “If your kokoro is true, your techniques will be correct.”

Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, often spoke of the four virtues of keiko: bravery, wisdom, love, and empathy.

Bravery is at the top of the list, for we need to be strong and determined enough to make a firm commitment to practice. We need valor to help us contend with all the obstacles that block our path.

Wisdom is acquired through deep meditation and wide-ranging study; wisdom enables us to make intelligent decisions and to maintain things in proper perspective.

When one’s practice is sound and balanced, a natural kind of love forms between one’s teacher and one’s fellow trainees. One also falls in love with his or her Way and becomes completely devoted to it. (Such affection can even extend to one’s training uniform. I was so fond of my keikogi that I mended and patched it until the cloth disintegrated: I sorely grieved the passing of what other people would think of as a rag.)

At the highest levels of training, a profound empathy is felt for all creatures, along with the fervent hope that everyone else, too, will be able to perfect their own Way. One of the meanings of Aikido is”Arm in arm let’s travel the Path together.” Like a bodhisattva, we want all others to reach the goal with us.

Sometimes a more concentrated effort is needed in our practice. Morihei wrote, “Iron is full of impurities that weaken it: through forging, it becomes steel and it is transformed into a razor sharp blade. Human beings develop in the same fashion.”

Such forging, tanren in Japanese, can take a variety of forms. For one of my kendo teachers, it consisted of 1,000 strokes (3,000 on Sunday) of a heavy sword every morning for nearly half a century. For one of my calligraphy teachers, it was copying the Heart Sutra 10,000 times. For me, it was 1,000 straight days of outdoor training at a mountain temple.

Morihei concluded, “In your training, do not be in a hurry, for it takes a minimum of ten years to master the basics and advance to the first rung. Never think of yourself as an all-knowing perfected master; you must continue to train daily with your friends and students and progress together in the Way of Harmony.”

Perhaps the most important element of Practice of the Way is transmission. Civilization is sustained by the person-to-person, heart-to- heart transmission of the cultural treasures of humankind.

I have had many fine teachers over the years but they all had one thing in common: through long years of shugyo they had become one with their Way. They taught by example—”what you are is far more important than what you say”—and they manifested the teaching in their entire being.

A real master truly delights in the Way. Even after sixty years of training, my Aikido teacher Rinjiro Shirata loved being in the dojo, and his favorite saying was, “Make the techniques anew each day!” Shirata Sensei was a peerless martial artist—when he was seventy- five years old he pinned Japan’s top pro wrestler—but the image that most lingers in my mind now that he is gone is his wonderful smile. It was the smile of enlightenment.

Source: http://www.lionsroar.com/the-practice-of-the-way/