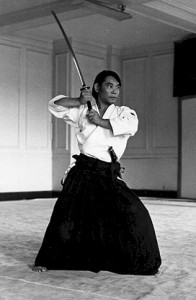

I found this article on aikidosphere.com on etiquette or Reigi-saho written by Kanai Sensei. In the late 1960s Sensei studied with Kanai Sensei in Boston while he was attending Harvard University. Sensei and Kanai Sensei would become friends and both shared a common interest in Aikido, swords and Iaido.

I found this article on aikidosphere.com on etiquette or Reigi-saho written by Kanai Sensei. In the late 1960s Sensei studied with Kanai Sensei in Boston while he was attending Harvard University. Sensei and Kanai Sensei would become friends and both shared a common interest in Aikido, swords and Iaido.

A Thought on Reigi Saho

by Mitsunari Kanai

Editor’s Note: Kanai Sensei's article on Reigi Saho is a classic, synthesizing an explanation of the philosophy and practice of Aikido's etiquette. It has been reprinted several times, for example in Aikido Forum and the USAF Newsletter, and we are happy to bring it to a new generation of readers.

Fundamental Philosophy of Reigi

The motivating principle of human survival, based upon the instinctual needs of food and sex, is power. The ability to effectively use power is crucial for the sustenance of life itself. The technology of fighting, pre-modern and modern, is an expression of this power, and the human race has survived to this point in history because of the ability to properly use this power. In fact, the development of this technology has given rise to new ideas, scientific advances, civilization, and culture. The basic principle of power is deeply rooted in life itself, and it is still the basis of human society as we know it today.

The student of Aikido, regardless of the reason, has chosen this particular form of martial art as his or her path, seeking to integrate it into daily life and undertaking the practice with dedication and constancy. Some people get enjoyment out of the Aikido training while some others get lost and fall into confusion. Some approach the training selfishly while others approach with modesty. Each person's approach to the training is a personal expression of his or her suffering and conflicts as a human being. Thus, the person applies his or her own judgment to Aikido and tries to give his or her own meaning to Aikido. The significance of Aikido, first of all, is that it is a martial art, but it also has meaning as the manifestation of natural laws and as a psychological, sociological, physiological, ethical, and religious phenomenon. All of these are overlapping, although each has its own unique identity, and together they constitute what we call Aikido.

If we pursue the combative aspect Aikido in our training, we can find extremely lethal and destructive power in Aikido. Therefore, if Aikido is misused, it can become a martial art of incomparable danger. Originally, martial arts meant this dangerous aspect. Aikido is no exception. Thus, any combative art unaccompanied by a strict philosophical discipline of life and death is nothing but a competitive sport.

While sports do not deal directly with life-or-death situations, they nevertheless advocate certain values necessary for building of character, for example, the observance of rules, respect for others, sportsmanship, proper dress and manners. This should be even more true and essential in the art of Aikido because Aikido deals with the question of life or death and insists on the preservation of life. In such an art is it not unquestionably appropriate to emphasize the need of dignified Rei in human interactions? Therefore, it is said that Rei is the origin and final goal of budo.

Some people may react negatively to this emphasis on etiquette as old-fashioned, conservative, and even feudalistic in some societies, and this is quite understandable. But we must never lose sight of the essence of Rei. Students of Aikido are especially required to appreciate the reason for and the meaning of Reigi-saho, for it becomes an important step towards misogi , which is at the heart of Aikido practice. I hope to discuss misogi in a future article.

At any rate, people working in martial arts tend to become attached to technical strength. They become arrogant and boorish, bragging of their accomplishments. They tend to make unpolished statements based on egoism. They immerse themselves in self-satisfaction. They not only fail to contribute anything to society but, as human beings, their attitudes are under-developed and their actions are childish. What is important about Reigi-saho is that it is not simply a matter of bowing properly. The basis of Reigi-saho is the accomplishment of the purified inner self and the personal dignity essential to the martial artist.

If we advance this way of thinking, the matter of Reigi-saho becomes the question of how one should live life itself. It determines what one's mental frame and physical posture should be prior to any conflict situation; the guard-posture must have no openings. Thus, Reigi-saho originates in a sincere and serious confrontation with life and death. Above all, Reigi-saho is an expression of mutual respect in person-to-person encounters, a respect for each other's personalities, a respect which results from the martial artist’s confrontations with life-or-death situations. The culmination of the martial artist's experience is the expression of love for all of humanity. This expression of love for all of humanity is Reigi-saho.

The martial artist's respect for the self and for others easily tends to become coarse and unpolished. So the idea of Reigi-saho, that each person is important, functions as a filter to purify and sublimate the martial artist's personality and dignity. Reigi-saho thus melts into a harmonious whole with the personal power and confidence that the martial artist possesses. This coming together establishes a peaceful, secure, and stable inner self which appears externally as the martial artist's personal dignity. Hence, a respectful personality with strength and independence is actualized. Therefore, Reigi-saho is a form of self-expression. The formalized actions of Reigi-saho reveal the total knowledge and personality of the martial artist.

We who are trying to actualize ourselves through Aikido should recognize that we are each independent. Only with such deep awareness of the self, can we carry out a highly polished Rei with confidence.

In short, Reigi-saho is to sit and bow perfectly and with dignity. In this formalized expression of Rei, there exists the martial artist's expression of self-resulting from his or her philosophy of life and death. And, for this reason, the martial artist shows merciful care and concern for those who walk on the same path. The martial artist shows merciful care and concern for all who seek to develop themselves in mind, body, and spirit, with sincere respect for other human lives.

In order for any external, physical act to be complete, it must be an expression of the total person. Abstractly, the external form includes the inside. This is a complete form. For Reigi-saho, that means that the external act was from the deep heart or mind. Also, the heart or mind was using the external act for its expression. This is a complete act. The formalized expression of the inner and outer person harmonized is the Saho of Reigi.

Saho (Formalized expression of Rei)

Reigi-saho thus contains varied implications regarding the inner life, but the observable form is a straightforward expression of respect for others, eliminating all unnecessary motions and leaving no trace of inattention. In the handling of martial art weapons the safest and most rational procedure has been formalized so that injury will not fall upon others as well as on oneself. Ultimately the formalized movements become a natural movement of the martial artist who has become one with the particular weapon. Below is an outline of the basics of Saho which I consider necessary knowledge for the martial artist.

1. Seiza (formal, Japanese-style sitting)

From your natural standing position draw your left leg slightly backwards (in some cases the right leg), kneel down on your left knee while staying on your toes. Then kneel on your right knee, lining up both feet while on your toes. Sit down slowly on both heels, as you straighten your toes, placing them flat on the floor so that you sit on the soles of your feet. Place either your left big toe on the right big toe, or have both big toes lightly touch each other side by side.

Next, place both hands on your thighs with fingers pointing slightly inward. Spread out both elbows very slightly but naturally, dropping the tension in your shoulders into the tanden or the pit of the stomach. Raise your sternum which will naturally straighten your back (do not stiffen your back), look straight ahead of you, and calm your body and mind for proper breathing. The space between the knees on the floor should be about the width of two or three fists.

2. Rei before the Kamiza (front altar)

From the seiza position slide both palms of your hands forward to the floor about a foot in front of you, forming a triangle, and then bow by lowering your face slowly and quietly towards the center of the triangle. Do not raise your hip or round your back as you do so; it is important to bend your body at the waist, keeping the back straight as possible. After a brief pause gradually raise your bowed head, pulling up both hands at the same time. Return both hands to the original seiza position and look straight forward.

3. Rei toward fellow students

From the position of the seiza first slide your left hand forward slowly, followed by the right hand, and place them on the floor about a foot in front of you and form a triangle, identical to the procedures described above. Following the bow, pull back your right hand while raising he body, followed by the left hand, and return to the original seiza position.

4. Rei towards teachers

The same etiquette as above is observed for bowing to your teacher, but the student should remember to lower his or her head in a bow before the teacher does, and to raise his or her own head after the teacher raises his or hers. Please remember that your bow shows your mental readiness.

5. Standing from the seiza position

First get on your toes, then begin to stand as you move your right foot (or left foot) half a step forward. Stand up slowly and quietly and pull back the right foot (or left foot) so that you are standing naturally.

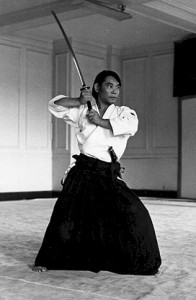

6. Saho when holding sword (applies also to other weapons such as bokken, jo, etc.)

The sword is normally placed on the sword stand with the handle to the left of you and the blade facing upward. (The side of the sword thus seen is called the front of the sword.) The placement of the sword is reversed for self-protection in cases of emergencies and when retiring at night.

(a) Rei to the sword (standing)

Take the sword from the sword stand with your right hand grasping the scabbard near the sword guard with the right thumb pressing the sword guard. Then turn up your right hand, placing the handle to your

right. Open your right palm holding the sword with the blade turned upwards, while at the same time the thumb of the left hand, palm down, holds the scabbard closer to the tip. The sword should be held up at eye level and the bow show be made slowly from the waist with the back kept straight. The sword is raised slightly during the bow.

(b) Rei to the Kamiza (standing)

From the standing bow to the sword, lower the sword in front of you thus bringing it closer to your body. With your right hand turn the handle upward

with the blade facing you. The sword is held vertically with the right hand in front of your center, and the left hand now grasps the scabbard immediately below the right hand. The right hand then is freed, permitting it to grasp the backside of the sword blade from above. The right hand thus grasping the scabbard should have its index finger placed on the back side pointing towards the sword’s tip. Hold the sword close to the right side of your body with the tip turned towards the front at a 35-degree angle with your right hand at your hip bone. Stand erectly and piously make your bow to the Kamiza. The bow should be about 45 degrees and you should pull your chin in while you bow.

(c) Rei in front of the Kamiza (sitting)

Sit in seiza. Place the sword on the floor on the right side of your body with the blade pointing toward you. The sword should be parallel to your body. Slide both hands simultaneously down from your thighs to the floor and bow to the Kamiza.

(d) Rei toward fellow students and teachers (sitting)

The same procedure should be followed as in the case above, except for the different sequence of putting your left hand down on the floor first when bowing and pulling up the right hand first when rising from the bowing position.

This concludes the description of the minimally required basics of Reigi-saho. The brevity of the explanations was intended to avoid possible confusion, but it may also have led to a lack of clarity and thoroughness of explanation concerning certain procedures. If I have not been generous enough in writing my description of Reigi-saho, then I hope that you will forgive me and give to me and others the chance to teach you more in the future.

http://www.aikidosphere.com/mk-e-reigisaho

The foyer of a traditional Japanese dojo or home is called the genkan (玄関). This area should be kept especially clean and neat.

When students come into the dojo, they should take off their shoes and arrange them neatly with the toes pointing out. If there is no more space left, they should put them in the geta-bako (下駄箱) or shoe rack with the toes facing in.

The foyer of a traditional Japanese dojo or home is called the genkan (玄関). This area should be kept especially clean and neat.

When students come into the dojo, they should take off their shoes and arrange them neatly with the toes pointing out. If there is no more space left, they should put them in the geta-bako (下駄箱) or shoe rack with the toes facing in.